une présentation de Daewoo en anglais avec un extrait du roman

Les voici en ligne, à l’attention des visiteurs anglophones de passage. Je lirai d’ailleurs la version française de cet extrait samedi 4 septembre, à Leicester, lors du colloque Social divisions in France and francophone world.

FB

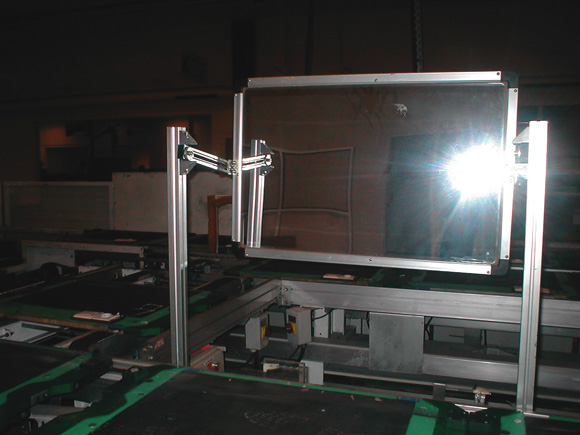

Photographies : déménagement de l’usine Daewoo à Fameck, novembre 2003.

François Bon | Daewoo, an introduction

One of our debts to American literature is a short fragment from William Faulkner (to the effect that “my own little postage stamp of native soil was worth writing about and that I would never live long enough to exhaust it”). It makes us understand that the chief difficulty is to find that little postage stamp, to recognize and accept it, before digging down to write.

I’ve always loved to read. Maybe it’s connected with having been nearsighted as a child and living in a tiny village with the sea for horizon. A novel is a dream, which reveals an otherwise inaccessible world.

I always try to have a project on the side. To work on my adolscence and the 1960s, I spent years putting together a biography of the Rolling Stones. Right now, I’m working on the 1970s, and some American friends are helping me trace the career of Led Zeppelin in your country.

If we chose our dream literature ourselves, it would fall flat. “Kill your darlings,” Faulkner also said. Twenty years after my first book, I find myself the author of a series of books that I did not choose to write. Prison. Mécanique. C’était toute une vie. In each case there was a death to honor—to be faced, because otherwise living becomes impossible, or at any rate it becomes impossible to write around the absence.

This was the case with Daewoo, very much so. First came the layoffs, then the sudden closing of the plant, and then I happened to read a couple of sentences in a newspaper, sentences pregnant with silence : “It made me crawl into a shell. I was on tranquillizers for months.” And that was it. You can’t go and ask the worker who uttered those sentences what they meant for her love life, her dreams, her insomnia, the empty hours of her day. They weigh on us, those few words, like dead weight, and our job is to give them their full amplitude, to put into them what we would put into them if it were a question of our own nights, our own children, our own lives. And then there are the other words that go along with these, the words of the homogenized language, the language of money, of the chamber of commerce, of industry : “Here as in other, similar towns, one finds an increase in the rate of suicide and divorce, as well as in the number of cancer cases.”

My friend Charles Tordjman, the director, and I borrowed a car from his theater and went to see for ourselves. Because the factory was so close. Because the invisible world had come knocking at our door. We bluffed our way into the empty factory. The assembly line was wrapped in plastic, like one of Christo’s art objects. All the signs, names, and faces were gone. When I returned a few weeks later, a truck with a crane was lifting the big sign with the name of the factory off the roof and putting it down on another truck, which hauled it away. To where ? That day I walked to a supermarket near the plant. bought a large notebook, and sat down for three hours in the cafeteria to write down everything I’d seen and heard.

Not all that much, to tell the truth. It’s a small town, a very small town, with its “Nails 2000” store (the year was 2003) and its “Future Driving School.” What to do ? Ask people what this upheaval meant to them ? No : write so as to extort from reality the symbolic violence that has been erased, rubbed out. I wrote in empty stairwells, in uninhabited apartment buildings. In hotel rooms. The full force of the violence had to be restored : I invented voices to get at what I didn’t understand in the words—each preceded by an arbitrary phrase. I said I’d recorded them on a Sony MiniDisc.

It’s literature’s job to convey the symbolic violence that reality erases. That is also part of what William Faulkner taught us.

How’s life ? (an excerpt)

When they invited us to be on How’s Life ? our friends said, “Yeah, lucky you.”

And others said, “Like they’re gonna care about your stupid stuff, they’re gonna look down on you, you won’t even see it coming …”

Three of us went. All expenses paid, supernice hotel. If I told you we weren’t nervous, I’d be lying. Everybody polite : smiles, little pats on the arm. People to stick mikes on you, fix your hair, offer you orange juice and coffee. The rich guys, they were down the other corridor. With their own makeup, their own orange juice. That was the idea of the show : you weren’t supposed to meet ahead of time.

Three against three, the moderator in the middle.

You’ve seen her on the tube a hundred times without really noticing. In person she’s not as big as you might think. She talks to you, a couple of sentences you think are meant for you, but while you’re thinking of how to answer, she’s already onto somebody else, repeating the same thing. So that was the idea : the rich and the poor.

And guess what : we were the poor.

The word had just gotten out about the end of Daewoo. The first company plan, and our first occupation, when we held the guy hostage. So they called the union and said they’d rather have girls who weren’t involved. Like, regular girls, you know ?

I’m in the union, but we told them I wasn’t.

The rich guys were three men, and they picked young ones on purpose. One had never worked a day in his life because he didn’t have to. “I could get used to that,” I said to the guy. On camera.

The TV people had shot a couple of short films. To show how things were where they lived, how things were where we live. Their kids getting driven to school in the car, you know, but like we’re on foot because the school is the one you see from the apartment building : stuff like that. When they film you taking your kids to school with their hair all combed and dressed up nice, what’s not to be proud of ? What difference does it make if three million people are watching or one : it’s you, taking your kids to school.

They weren’t about to show you the kind of rich people you read about in the papers, they didn’t want that, it had to be rich people like you and me : so you see this guy coming home at night after his workout, and he pours himself a drink in a living room with a TV as big as a movie screen. And after that, in the other film, it was Evelyne’s husband, and they’d asked him to fix himself a drink, his cocktail and three bottles in that bar he built himself. Yeah, go ahead and smile. He was nice, too, Evelyne’s husband, he offered the film crew a drink.

And the rest, you know, it was all like that.

Fill up the old Renault at the supermarket in one, in the other some German car where you turn on the radio with the push of a button. That was for openers. Them sitting around on a patio, us milling around the factory lot in the morning at the starting whistle because nothing is going on inside the plant, they said because there were no supplies, but we went to work anyway just to make them pay us to the end.

After that I have no idea. It’s a world where everything is shiny, the lights are very bright, and it’s always straight ahead, no turning back.

Some of the questions you could expect : them with their nicely shaved cheeks, born with silver spoons in their mouths and not about to cough them up, and us, from another world.

What got to me, you know, wasn’t the clothes or the glitz or anything, it was our faces, the difference you could see : that you carry so much baggage around with you, that says who you are and what you do.

They might have asked, I don’t know, what would you do if you could live for three days the way they do, and vice versa. But no, they made us talk about cooking, and she wanted us to say things about our love life. Our habits, and like what we did in bed, why not ? The guy with the BMW, he was against marriage. That was their philosophy. We dreamed of going places, and the guys on the other side, they’d already been and were bored. And really they were all right, those guys, the girl from the show told them three times she would have preferred guys with claws, small-minded guys. We don’t make our enemies.

She had us talk about what pissed us off. That we could do. We knew what got to us. They were more, like, noble : when you’re not pissed off at your boss, you can get all high-minded and talk about how you hate dictators and stuff.

Like they were saying : see, those girls, they fit the part.

I felt damp and said to myself, You’re sweating, don’t let them see. I thought : my friends are watching, my mom’s watching, I gotta get out of here.

When the three guys talked, they pointed the cameras at our faces to see what we were thinking, how we were reacting. They showed our legs, and you know what else ? the chain on my wrist and Josiane’s rings. You didn’t see the guys’ ankles or whether they were listening when we talked. Or the smiles, or the whispers : the redhead, she’s hot, no ?

What did she want, the girl from the show ? For us to all get up at once, three guys and three girls, and hug in front of everybody and say stuff like, We’re sorry, we had the wrong idea about you, the world shouldn’t be like that …

One of the guys explained that it was basically our fault, that you have to be ready to move, to go live in Nice or Germany, and in my head I was like smiling, for them life was so simple. Finally Josiane said we didn’t give a damn about the money, we didn’t care about eating or paying the rent either, what mattered was freedom and self-respect, but the girl didn’t let her finish her sentence : she announced that next week there would be something or other about sexuality. We figued out that the three guys were planning to take the girl from the TV out to dinner (well, anyway, it was Josiane who figured it out, she went and took a look down the other corridor : Josiane always has an eye or an ear out), but we weren’t invited.

Before going back to the hotel, we went out for a drink, three women, like grown-ups, in Paris : big deal, right ? The next day in the train, we didn’t talk much.

You feel things because of who you are. You brood. The hard thing is time passing. All the simple things that used to be your life, the little fun things you bought yourself, something to wear, a movie.

With this in your head, that there’s nothing certain about starting over.

You don’t say that to anybody else.

The day after the show, I saw Sylvia and asked her what she thought. She hadn’t watched, is what she told me.

Fine, going on TV to talk about Daewoo, to talk about who we are—what were we supposed to do, say no ?

diffusion sous licence Creative Commons CC-BY-SA

1ère mise en ligne 1er septembre 2013 et dernière modification le 9 décembre 2013

merci aux 5254 visiteurs qui ont consacré 1 minute au moins à cette page